Joe Biden’s harsh labelling of national leaders makes geopolitical solutions even more elusive. The ANC’s vilifying successful societies undermines our economic prospects.

Being quick to judge makes it difficult to understand others. Cooperation suffers and conflicts harden. The ANC’s criticism of successful countries mostly reflects its prioritising patronage ahead of national interests.

His campaign trail supporters would roar their approval when candidate Biden vowed to make Saudi Arabia’s crown prince an ‘international pariah’ for the brutal slaying of journalist and dissident Jamal Khashoggi. After Russia invaded Ukraine, President Biden visited Riyad only to be rebuffed. China’s President Xi then recruited Saudi Arabia’s support for its pro-authoritarian challenges to the prevailing world order. This led to Xi playing peacemaker between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Many Biden supporters also approve of his labelling his Russian counterpart a ‘war criminal.’ Meanwhile, he repeats ‘we will defend every inch of Nato.’ As errant projectiles and mid-air provocations have shown, the potential looms large for an ‘incident’ violating a Nato country’s sovereignty.

As the US is critical to supplying Ukraine and maintaining sanctions on Russia, ending the war largely hinges on the US and Russian presidents striking a deal. Biden’s labelling Putin a war criminal highlights why, in stalemated negotiations, a change in leadership often provides an opening.

As the US presidential election approaches, Putin will become even less interested in negotiating with the Biden administration. The dynamics somewhat resemble Iranians holding 50 members of the US embassy hostage for 444 days until just after Reagan, having defeated Carter, was sworn in as president.

Even those who align with Biden’s politics should be concerned by his global-stage virtue signalling. Rather, underlying attitudes of ‘we are better than them’ is rife among US progressives and it explains much of that country’s stark political polarisation.

No solutions being debated

Our political processes also suffer from issues being routinely framed as moral challenges. A prime example is the ANC’s success at framing our youth unemployment crisis as a tradeoff between fiscal rectitude and the compassion to provide sub-subsistence payments. There are no solutions being debated and economists don’t predict noticeable improvements.

Whether at a G7 summit, a work-related conference or a teacher-parent conversation, judging others can undermine understanding and cooperation. Many are quick to judge former US president Richard Nixon, yet he sought to understand China’s leader Mao Zedong. The resulting diplomatic breakthrough led to a billion people being uplifted from extreme poverty.

While comparing Mao to Putin is hardly a straightforward exercise, it is fair to say that Mao ruthlessly killed far more innocent people. Prior to meeting him, Nixon publicly referred to Mao as a ‘great revolutionary leader’ and a ‘great man’. In conversations with his advisors, Nixon described Mao as ‘crazy’ and ‘a monster’ while expressing concern about the instability that could result from his eventual death.

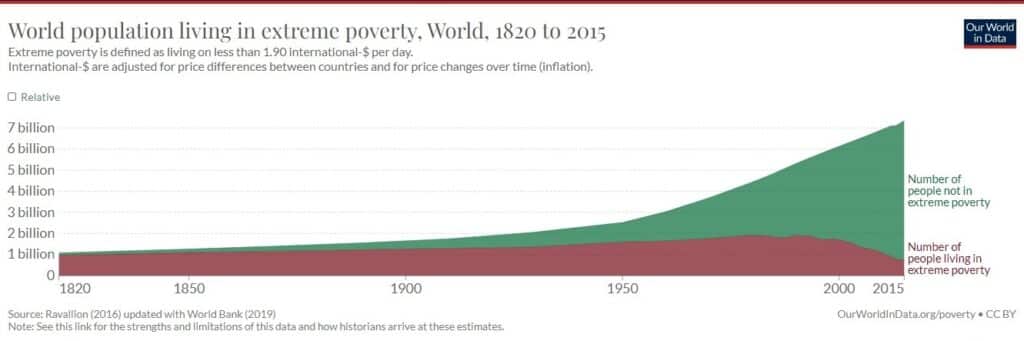

Those in free societies can openly criticise but this doesn’t mean that overindulging such criticisms is cost-free. Many people can list numerous Western and US missteps and injustices. Far fewer appreciate that two centuries ago, there were just over a hundred million people not living in extreme poverty.

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/world-population-in-extreme-poverty-absolute

By the time of the Great Depression, just over a hundred years later, nearly seven hundred million people were not living in extreme poverty. Within a decade the Second World War would provoke the subsequent era of US leadership. Today, over seven billion people do not live in extreme poverty.

As so few people appreciate how this was achieved, attempts by authoritarian regimes, like China and Russia, to reshape the global order are often welcomed as worthy challenges to a Western-shaped global order. But while attempts by Western powers to maintain peace and expand global prosperity have always been flawed, the leaders of China and Russia offer a vastly inferior alternative. Those most at risk are those living in extreme poverty.

Extreme poverty

Sub Saharan Africa accounts for 15% of the world’s population and over 70% of its extreme poverty. Those who are quick to judge often revel in Marxism, as his worldview was informed by lenses focused on class, conflict and oppression. They lay the blame on colonialists despite the fact that nearly all countries have been colonised.

Those interested in solutions will want to understand how thirty years of post-colonialism have resulted in what had been this region’s economic hegemon, South Africa, achieving the world’s worst level of entrenched youth unemployment while over a billion Asians were escaping extreme poverty. Three related words explain much: beneficiation, localisation and diffusion.

Economists can’t take the term ‘beneficiation’ seriously as the concept is as commercially bogus as it is politically contrived. Locating production facilities near raw material deposits tends to be very inefficient. Conversely, it can be very appealing to those running patronage-focused governments of resource-endowed nations.

Interest rates must sometimes rise to choke inflation. Near-term growth suffers in order to maximise long-term growth. Indulging ‘localisation’ policies involves similar but even harsher near- versus long-term tradeoffs with growth and employment. Policy makers in successful countries accept this.

Whereas assembly lines once drove global growth, today’s core growth driver is the mix of global integration and disruptive innovations. This harshly constricts the inherently limited potential for bottom-up growth – particularly within an African township. Rather, sustaining high growth requires a top-down approach where poorer countries add value to exports for wealthier countries.

Asia’s phenomenal progress over the last half century traces to geopolitical progress permitting the ‘diffusion’ of scientific and commercial advances leading to many hundreds of millions of Asian workers becoming vastly more productive. Africa’s participation has been very modest mostly due to geographic isolation being amplified by the predatory practices of patronage-focused governments.

Stay in power

China, Russia and other authoritarian governments want to block Western efforts to diffuse the productivity enhancements which provoke broad upliftment. Their pitch to predatory regimes distils to: align with us and you can stay in power without worrying about pesky things like accountability or legitimate elections.

There is little appreciation that both global inequality and poverty have been plummeting in recent decades. This would detract from the popular blame-the-rich narratives.

Diffusing productivity-enhancing skills and tools is more commercially robust when executed on a grand scale. This requires access to large affluent markets. Otherwise the pace of development slows to a trickle.

The unspeakable implication is that inequality is a vital component for sustaining high-volume upliftment. Yet what is required is not the creation of small pockets of extreme wealth but rather large middle class countries with abundant discretionary income. This describes the political grouping of countries termed ‘the West.’

Creating predominantly middle class societies is quite difficult and it is harder still for authoritarian societies as they are so prone to supporting patronage and avoiding accountability. Russia’s moderate success at creating a large middle class has benefited from massive resource wealth and considerable scientific capabilities.

Rising productivity

China’s mix of authoritarianism and raw capitalism has been extraordinarily successful when measured by its manufacturing competitiveness in many major segments. Yet China is still far from having sufficient domestic discretionary purchasing power to maintain steady growth without running a trade surplus. But, and unlike South Africa, its growth relies on value-added exporting and this provokes rising productivity and high employment.

South Africa has self-sanctioned itself with localisation and anti-competitive policies to achieve a situation resembling Russia’s. Exporting commodities to China can keep in power increasingly authoritative and patronage-focused governments. It is vastly less effective at creating jobs.

Commodity exporting is great for governments that don’t want to hold legitimate elections or be held accountable. Large middle class societies tend to be quite demanding about both.

Chinese leaders see much polarisation and they presume the US and the West are in decline. Western countries are so dogmatically anti-inequality that they have resisted aggressively using their vast discretionary spending power as a carrot or stick. There are no scenarios where we can afford our localisation policies.